Rep. Brady Brammer acknowledges he’s not the type to run legislation on psychedelics.

Continue readingNuminus Wellness Prepares For An MDMA Clinical Trial

Numinus Wellness recently announced important milestones in its clinical trial of MDMA-assisted therapy to treat individuals suffering from PTSD.

Continue readingNew Psychedelics Legalization Bills Introduced In Virginia, Kansas And Missouri | Benzinga

A wave of psychedelics legislation continues to sweep across the country.

Recently, lawmakers in Virginia and Kansas

Continue readingResearch in 60 Seconds: How Taking Psychedelics Can Be Therapeutic | University of Central Florida News

Research in 60 Seconds: How Taking Psychedelics Can Be Therapeutic | Read more about UCF Arts & Culture, Colleges & Campus, Medicine, Research, Orlando and Central Florida news.

Continue readingEntheon Biomedical Subsidiary, HaluGen Life Sciences, Announces Agreement with Psychedelics Today

Expanding brand awareness and access to HaluGen’s Psychedelics Genetic Test Kit Vancouver, British Columbia–(Newsfile Corp. – January 18, 2022) – Entheon Biomedical Corp. (CSE: ENBI) (OTCQB: ENTBF) (FSE: 1XU1) (“Entheon” or the “Company”), a biomedical company focused on the research and development of psychedelic drugs and leading-edge biomarkers to provide personalized treatment of addiction disorders, has announced an agreement with Psychedelics Today, LLC (“Psychedelics Today”) to help dri

Continue readingVirginia Lawmakers Propose Decriminalizing Psilocybin And Other Psychedelics | Benzinga

Virginia lawmakers, Del. Dawn Adams (D), and Sen. Ghazala Hashmi (D) along with Sen. Jennifer Boysko (D)

Continue readingPandemic Tripping With Psychedelics

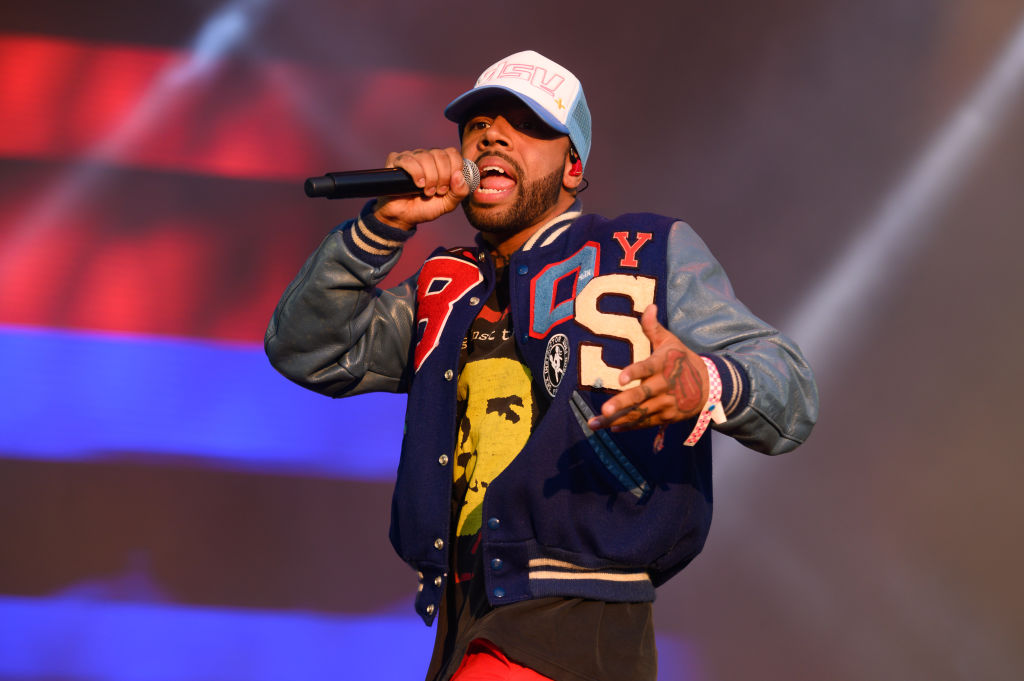

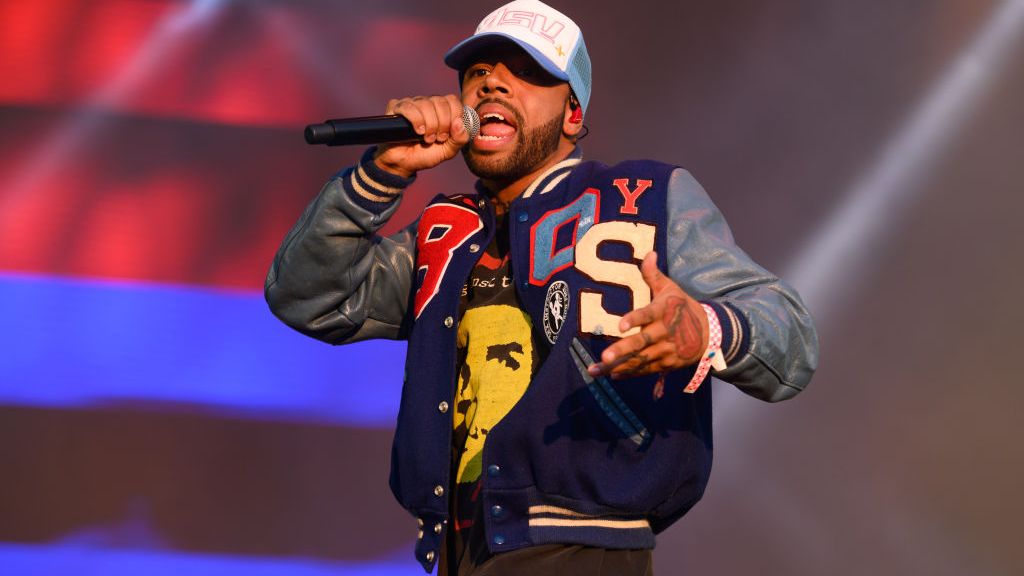

Rapper Vic Mensah Arrested At Dulles Airport After Psychedelics Found

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS – SEPTEMBER 18: Vic Mensa performs during Riot Fest 2021 at Douglass Park on September 18, 2021 in Chicago, Illinois. (Photo by Daniel Boczarski/Getty Images)

Dulles, Va. (WJZ) — Rapper Vic Mensah was arrested at Washington Dulles International Airport on Saturday after U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers found illicit narcotics in his baggage.

Victor Kwesi Mensah, 28, arrived at the airport via a flight from Ghana at about 7 a.m. on Saturday.

READ MORE: Mosby’s Attorney Says She Was Advised Retirement Account Withdrawals Were Permitted

Federal officers found 41 grams of liquid LSD, about 124 grams of Psilocybin capsules, 178 grams of Psilocybin gummies, and six grams of Psilocybin mushrooms concealed inside his luggage, according to a government press statement.

Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority Police officers confiscated the narcotics and charged Mensah with felony narcotics possession charges, federal officials said.

READ MORE: Ravens Re-Sign CB Kevon Seymour For 2022

He has been active in the music community since 2013. During that time he has partnered with artists like Kanye West and Sia.

Mensah has won three awards—an NAACP Image Award for outstanding new artist, a Grammy Award for best rap song, and an mtvU Woodie Award for best video.

Narcotics possession remains illegal under federal law and all travelers are subject to that law when departing and arriving at America’s ports of entry.

MORE NEWS: Some Struggle With Power Outages After Winter Storm Pelts Baltimore Region

CBP processes more than 650,000 travelers who arrived at airports, seaports and land border crossings per year, according to the press statement. Its officers arrest about 25 wanted criminals at ports of entry every day.

Psychedelic use is only “weakly” associated with psychosis-like symptoms, according to new research

People who take psychedelics are more likely to report psychosis-like symptoms, but this is largely explained by the presence of other mental health conditions and the use of other psychoactive drugs. This finding comes from a study published in the journal Scientific Reports, which further found improved evidence integration and greater flexibility of fear learning with psychedelic exposure.

Psychedelics are a class of drugs that produce hallucinogenic effects and can alter perception, mood, and cognition. The most common psychedelics include LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), and psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”). In recent years, scientific studies have pointed to the potential therapeutic effects of these drugs, but surprisingly few studies have examined the possible harmful psychological effects.

While it has been suggested that psychedelics can provoke the “development of prolonged psychotic reactions”, larger studies have found no such evidence. A research team led by Alexander V. Lebedev wanted to re-explore this question among a young, healthy non-clinical population. They proposed that it would be easier to identify sub-clinical expressions of psychopathological traits, such as cognitive biases found along the schizophrenia spectrum, among a non-psychiatric group.

The researchers distributed a survey to 1,032 Swedish adults, of whom 701 were between the ages of 18 and 35 and had no psychiatric diagnoses and no history of brain trauma. The questionnaire included a measure of schizotypy — a personality trait that includes schizophrenia-like characteristics such as disorganized thinking and paranoid thoughts.

When comparing psychedelic users to non-users, average schizotypy scores among users were significantly higher, but the effect size was small. Furthermore, when looking exclusively at the subsample of healthy participants, the effect was only marginally significant. Finally, when taking co-occurring drug use into account, the effect of psychedelic use on schizotypy was no longer significant among either sample.

A follow-up survey among a subsample of 197 participants examined drug use patterns and found no evidence of heightened schizotypy among those with greater exposure to psychedelics. However, the use of stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamines was a robust predictor of higher schizotypy.

To explore causal effects, the researchers also conducted a behavioral study among a subset of 39 of the participants. The sample was made up of 22 psychedelic users and 17 age/sex-matched non-users. Participants completed a task to measure Bias Against Disconfirmatory Evidence (BADE) — a cognitive bias common along the schizophrenia spectrum. The task asked subjects to rate the plausibility of different interpretations of a scenario and assessed the BADE facet of Evidence Integration Impairment (EII) or “lack of ability to modify beliefs when facing new information.”

Surprisingly, psychedelic exposure actually predicted lower Evidence Integration Impairment scores, while the use of stimulants predicted greater Evidence Integration Impairment. These results, the authors say, “support the rationale of psychedelic-assisted therapy for non-psychotic psychiatric conditions characterized by overly fixed cognitive styles, such as, for example, depression.”

The participants also completed a reversal learning task that measured their fear responses to a conditioned stimulus that was sometimes presented with a mild electric shock, according to changing rules. After controlling for co-occurring drug use, people with greater overall psychedelic exposure showed higher sensitivity to instructed knowledge — suggesting greater flexibility of fear learning. Lebedev and his colleagues say that this may suggest that psychedelics can “augment top-down fear learning in a lasting way, which, in turn, may explain their particular efficacy in treating anxiety and trauma-related psychiatric disorders.”

Overall, the findings suggest only a weak link between psychosis-like symptoms and psychedelics. “Our analyses did not support the hypothesis that psychedelics may pose serious risks for developing psychotic symptoms in healthy young adults,” the authors say, although they specify that, “the lack of a strong relation between use of psychedelics and psychosis-associated symptoms does not preclude that such drugs are detrimental for individuals with a high risk of developing psychotic disorders—an important question that needs to be investigated in future studies.”

The study, “Psychedelic drug use and schizotypy in young adults”, was authored by Alexander V. Lebedev, K. Acar, B. Garzón, R. Almeida, J. Råback, A. Åberg, S. Martinsson, A. Olsson, A. Louzolo, P. Pärnamets, M. Lövden, L. Atlas, Martin Ingvar, and P. Petrovic.

Top Federal Drug Official Says ‘Train Has Left The Station’ On Psychedelics As Reform Movement Spreads

A top federal drug official says the “train has left the station” on psychedelics.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Director Nora Volkow said people are going to keep using substances such as psilocybin—especially as the reform movement expands and there’s increased attention being drawn to the potential therapeutic benefits—and so researchers and regulators will need to keep up.

The comments came at a psychedelics workshop Volkow’s agency cohosted with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) last week.

The NIDA official said that, to an extent, it’s been overwhelming to address new drug trends in the psychedelics space. But at the same time, she sees “an incredible opportunity to also modify the way that we are doing things.”

“What is it that the [National Institutes of Health] can do to help accelerate research in this field so that we can truly understand what are the potentials, and ultimately the application, of interventions that are bought based on psychedelic drugs?” Volkow said.

The director separately told Marijuana Moment on Friday in an emailed statement that part of the challenge for the agency and researchers is the fact that psychedelics are strictly prohibited as Schedule I drugs under the federal Controlled Substances Act.

“Researchers must obtain a Schedule I registration which, unlike obtaining registrations for Schedule II substances (which include fentanyl, methamphetamine, and cocaine), is administratively challenging and time consuming,” she said. “This process may deter some scientists from conducting research on Schedule I drugs.”

“In response to concerns from researchers, NIDA is involved in interagency discussions to facilitate research on Schedule I substances,” Volkow said, adding that the agency is “pleased” the Drug Enforcement Administration recently announced plans to significantly increase the quota of certain psychedelic drugs to be produced for use in research.

“It will also be important to streamline the process of obtaining Schedule I registrations to further the science on these substances, including examining their therapeutic potential,” she said.

At Thursday’s event, the official talked about how recent, federally funded surveys showed that fewer college-aged adults are drinking alcohol and are instead opting for psychedelics and marijuana. She discussed the findings in an earlier interview with Marijuana Moment as well.

Don’t miss out on the @NIDAnews, @NIAAAnews, & @NIMHgov-sponsored virtual Workshop on Psychedelics as Therapeutics: Gaps, Challenges, and Opportunities, Jan. 12‒13, 2022. Learn more and register: https://t.co/S1zttkoYXq pic.twitter.com/C2Qrk6FN9a

— NIDAnews (@NIDAnews) January 10, 2022

“Let’s learn from history,” she said. “Let’s see what we have learned from the marijuana experience.”

While studies have found that marijuana use among young people has generally remained stable or decreased amid the legalization movement, there has been an increase in cannabis consumption among adults, she said. And “this is likely to happen [with psychedelics] as more and more attention is placed on these psychedelic drugs.”

“I think, to a certain extent, with all the attention that the psychedelic drugs have attracted, the train has left the station and that people are going to start to use it,” Volkow said. “People are going to start to use it whether [the Food and Drug Administration] approves or not.

There are numerous states and localities where psychedelics reform is being explored and pursued both legislatively and through ballot initiative processes.

On Wednesday—during the first part of the two-day federal event that saw nearly 4,000 registrants across 21 time zones—NIMH Director Joshua Gordon stressed that his agency has “been supporting research on psychedelics for some time.”

Tune in today and tomorrow for the @NIH workshop on Psychedelics as Therapeutics, which will examine findings on psychoplastogens for treating depression, post-traumatic stress, and substance and alcohol use disorders. https://t.co/Qzxte5xJt9

— Joshua A. Gordon (@NIMHDirector) January 12, 2022

“We can think of NIMH’s interests in studying psychedelics both in terms of proving that they work and also in terms of demonstrating the mechanism by which they work,” he said. “NIMH has a range of different funding opportunity announcements and other expressions that are priorities aimed at a mechanistic focus and mechanistic approach to drug development.”

Meanwhile, Volkow also made connections between psychedelics and the federal response to the coronavirus pandemic. She said, for example, that survey data showing increased use of psychedelics “may be a way that people are using to try to escape” the situation.

But she also drew a metaphor, saying that just as how the pandemic “forced” federal health officials to accelerate the development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines because of the “urgency of the situation,” one could argue that “actually there is an urgency to bring treatments [such as emerging psychedelic medicines] for people that are suffering from severe mental illness which can be devastating.”

But as Volkow has pointed out, the Schedule I classification of these substances under federal law inhibits such research and development.

The official has also repeatedly highlighted and criticized the racial disparities in drug criminalization enforcement overall.

Delaware Lawmakers File New Marijuana Legalization Bill With Key Equity Revisions